Lucas Cranach the Elder made an impression on the Reformation not through his ideas, his books, or his ecclesiastical service, but his art. As the Saxon court painter in Wittenberg for Frederick the Wise, he produced many works of art that were emblematic of Protestant theology at the time of the Reformation. He also became intimate friends with Luther, both of them standing in turn as godparent to a child of the other, and is responsible for the most famous portraits of the reformer. He also aided the spread of the Reformation itself through the many woodcuts that adorned Protestant books and gained popularity due to the influence of the printing press.

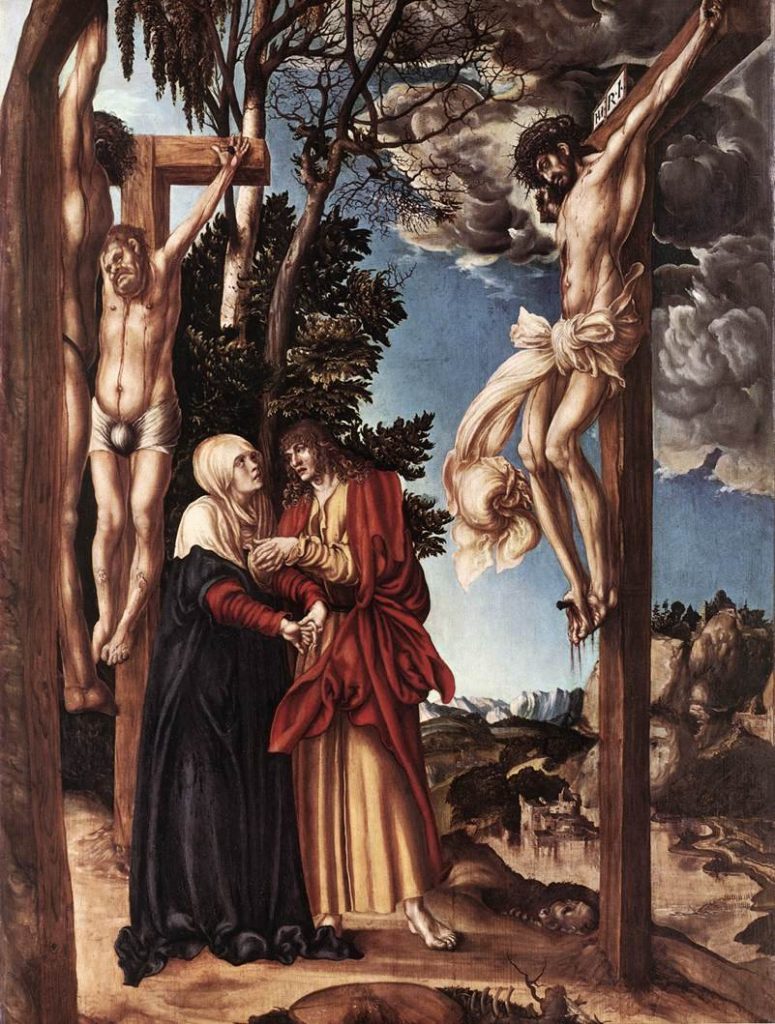

Born in 1472 in Kronach near Bamburg, Cranach took the name of the town for his own. He was born to a painter father, Hans Maler, under whom he presumably apprenticed. By roughly 1501, the young artist had made his way to Vienna, where he mingled in humanist circles. His most famous painting of the era, 1503’s Crucifixion, reflected his early association with the so-called Danube School. This approach was characterized by an emphasis on natural landscape and the human subject’s relationship to nature, in this instance the image of Christ’s crucifixion set against the backdrop of a lush landscape. It was in 1504, however, that Cranach received an invitation to join Frederick the Wise’s court in Wittenberg as his personal artist. He would spend the remainder of his life under the patronage of three electoral Saxony princes—Frederick, John the Steadfast, and John Frederick the Magnanimous—as their court painter.

In the early years at Wittenberg, Cranach’s work was largely restricted to paintings commissioned by Frederick the Wise. By 1507, he had opened a studio with at least one student working under him. A year later, Frederick presented him with a coat of arms featuring a winged serpent. The image became Cranach’s signature the rest of his career, adorning paintings and printed works alike. In 1509, after a trip to the Netherlands during which he reportedly painted the visage of the future Habsburg emperor Charles V, he constructed the so-called Torgau altarpiece. Titled the Holy Kinship, it featured prominent European rulers such as then-emperor Maximillian, Frederick the Wise, and Frederick’s son, John the Steadfast, as members of Christ’s holy family.

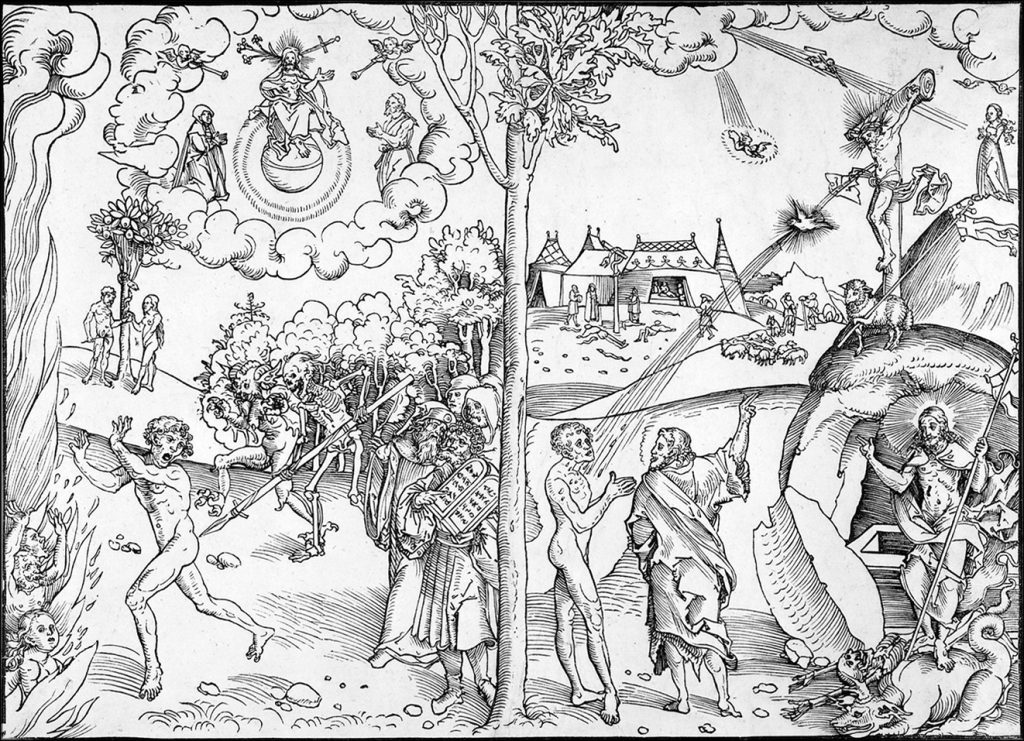

Cranach’s work took on a new direction, however, with the onset of the Protestant Reformation. Serving in the court of Luther’s protector and coming to know the young reformer personally, Cranach became a purveyor of Protestant thought and reform through his paintings and woodcuts. The woodcuts in particular decorated many of the treatises published by the Wittenberg reformers and functioned as visual conduits for their theology. The first such woodcut, in a 1519 pamphlet, featured a contrast between the chariot to heaven and the chariot to hell. On 1521, Cranach published 13 woodcuts by the title, Passional Chrisi und Antichristi, which this time contrasted the life of Christ with the luxurious lifestyle of pope and curia. The most famous woodcuts were printed in Luther’s German translation of the scriptures. Beginning in 1522 with the German New Testament, with the Old Testament following in 1524, Cranach’s images took on a crucial catechetical function though their representation of biblical passages in the Luther Bible.

The most enduring images Cranach produced remain the portraits he painted of Luther, many of which still adorn books of the Wittenberg theologian’s writings. He first portrayed Luther in 1520 in his Augustinian habit. A year later, Cranach depicted him by contrast in his university doctor’s cap. He also produced the woodcut of Luther in full beard while hiding in the Wartburg under the pseudonym Junker Jörg, or Knight George. Cranach continued serving Luther and his family, drafting the wedding portrait of Luther and Katherina von Bora (whom the court artist had earlier sheltered after she fled her Benedictine convent) and in 1527 painting images of both Luther’s parents.

Cranach’s later work continued to embody Protestant theological themes. His most famous, the 1529 Allegory of Law and Grace, was produced as both a woodcut and a panel painting. It featured on one side the crucifixion as a blessing to the faithful, on the other side the torment of those under the old law. Later, in 1538, he fashioned what would become a common Protestant image, Christ Blessing the Children. The painting emphasized both the primacy of faith within Protestant theology and the affirmation of infant baptism against the Anabaptists.

Despite his clear personal commitment to the theology of the reformers, Cranach nonetheless supplied works to Luther’s opponents. Most prominently, he drafted 180 paintings for Albrecht of Brandenburg, the Hohenzollern prince who occasioned the indulgence controversy when he obtained the bishopric of Mainz and received the right to sell indulgences from Leo X in order to pay off the debt he incurred to come up with the appropriate fees. Likewise, Cranach crafted numerous altarpieces for churches throughout the region that remained aligned with Rome, such as those in Halle in 1523 and Freiburg in 1524. Beyond that, he served other Saxon nobility with paintings that often bordered on the scandalous or sensual, including Greek deities and nudes.

Cranach’s productivity made him a prominent—and very wealthy—figure in Wittenberg. According to tax records of 1528, he was the town’s second wealthiest citizen. He employed many artists in his studio who painted the works he sketched for them, thus increasing his productivity. Two of his sons, Hans (1513–37) and Lucas (1515–86), worked alongside him. In addition to the income he received from his artwork, Cranach also owned a pharmacy, wine store, bookstore, and a printer’s shop. From 1519 until 1545, he served on the Wittenberg city council, at least twice governing as its Bürgermeister (1537 and 1540), or mayor. His time in Wittenberg came to an inauspicious end when his patron, John Frederick, was imprisoned at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547. He followed John Frederick into exile, first at Augsburg in 1550, then Innsbruck, and finally Weimar in 1552. Cranach lived in Weimar with his son-in-law, Christian Brück, until his death on October 16, 1553. The inscription on his tombstone in Weimar reads “pictor celerimus”—the swiftest painter.