A humanist, reformer, and theologian, Andreas Osiander embodied the various circles in which many Protestants ran, but also the complicated relationship between those various circles that led to tensions and divisions within the Reformation. A trained humanist, he would master Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, study the Jewish Kabbalah, and produced his own revision of the Latin Vulgate and a harmony of the Gospels. He also became an early supporter of Luther’s reforms, which eventually led to adopting reform in his own city, advocating for the Protestants at imperial diets, and drafting numerous evangelical church orders. More famously, however, he grew critical of the Wittenbergers and departed from them on a number of issues, above all the question of the relationship between justification and sanctification.

Though his exact date of birth is unknown, Osiander hailed from the Franconian town of Gunzenhausen, presumably born in December of either 1496 or 1498. He entered Ingolstadt in 1515, there learning Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic. He also came under the influence of the controversial humanist Johannes Reuchlin, who was the uncle of Philipp Melanchthon. Reuchlin led Osiander to study Kabbalah, a form of medieval Jewish mysticism. In 1520, Osiander was ordained and shortly thereafter began teaching Hebrew at the Augustinian monastery in Nuremberg. During his time there, he began work on revising the Latin Vulgate from the original Greek, which he would bring to completion and publish in 1522.

The same year, he was also appointed preacher at St. Lorenz parish church in Nuremberg, a position he would occupy until 1548. He emerged as an early champion of reform in the region. By 1523, he helped establish communion in both kinds. He also presented the case for the evangelical reforms before the city council, which not only adopted it, but named Osiander its principal theological advisor. He availed himself of evangelical freedom when he married in 1525—the first of three wives he would bury. His most significant practical contribution to the Nuremberg reforms came in the shape of a 1533 church order, adopted by both Brandenburg and Nuremburg. Alongside the 1533 order, he would publish a collection of children’s sermons intended for catechesis in evangelical doctrine. He also initiated a substantial controversy in the diocese after the publication of his church order, when he insisted that private confession replace the general form of corporate confession. In 1543, Count Palatine Ottheinrich requested a church order, which Osinder penned for Palatine-Neuburg, basing it on his own 1533 version.

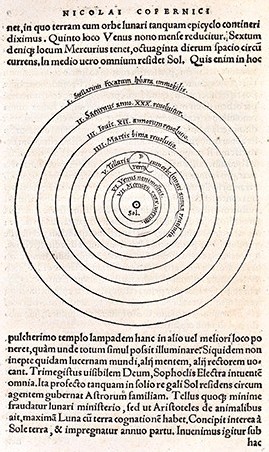

Despite his ecclesiastical commitments, Osiander continued his humanist efforts on a number of fronts. He composed a harmony of the Gospels in Greek in 1537, Harmonia Evangelica, in which he endeavored to show that the four evangelists did not contradict one another. He maintained an interest in Hebrew language and literatures, even drafting an anonymous tract in 1540 that defended Jews against a prevalent allegation of killing Christian children and drinking their blood. Then in 1542, he published Nicholas Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus Orbium Caelestium along with an unauthorized preface. The preface claimed the text was only a hypotheses to make it more palatable to its prospective audience.

Osiander also emerged as a noted political advocate for reform more broadly. He had defended Luther’s cause against the Edict of Worms at the Nuremberg diets in 1522 and 1524, which eventually led to a temporary suspension of the Edict of Worms in lieu of a general council. Osiander also helped convert Albrecht of Prussia, who would become his advocate and patron later in life. He remained active representing the evangelical movement on various imperial stages. Yet as time passed, the Nuremberg theologian grew increasingly at odds with the Wittenberg contingent he had set out to support. While he defended Luther’s position on the Eucharist at the 1529 Marburg Colloquy, he began to grow openly critical of Luther and the Wittenberg theology at the 1530 Diet of Augsburg, the 1537 Schmalkalden Assembly, and the 1539–40 colloquies at Hagenau and Worms.

In 1548, Nuremberg accepted the Augsburg Interim proposed by Charles V, which would have forced Protestants to accept the traditional Catholic ceremonial, offering them in return only the chalice and clerical marriage as concessions. Osiander objected and fled the city, first to Breslau, and then to Königsberg in East Prussia under the protection of Albrecht of Prussia. Against protestations, Albrecht named Osiander both pastor of the city church and university professor. Controversy followed close behind. In his inaugural disputation, Osiander criticized Philipp Melanchthon’s emphasis on forensic justification against an unconvinced opponent, one Martin Chemnitz. Osiander had begun teaching that justification necessarily included sanctification. Moreover, this sanctification comes about only through the indwelling of Christ’s divine nature, not his human nature, thereby eliciting charges of Nestorianism. He also attempted to resuscitate the contested view of John Duns Scotus that God would have become incarnate even without the fall of men into sin. But it was his view of justification that became a subject of debate waged well past his death on October 17, 1552, and marred his legacy within the Lutheran tradition. At the behest of Albrecht, an examination of Osiander’s teaching began, and with little opposition eventually resulted in the 1577 Formula of Concord explicitly rejecting his view of justification and sanctification in its third article.