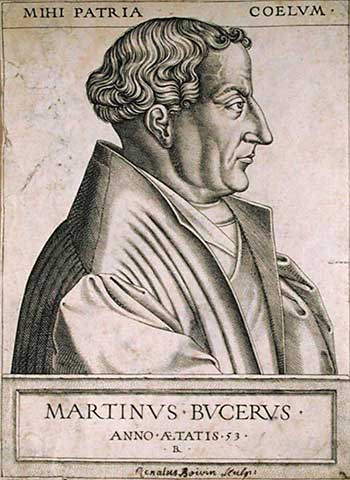

While not as recognizable as contemporaries Martin Luther, John Calvin, Ulrich Zwingli, or even Philipp Melanchthon, Martin Bucer’s influential role in the early Protestant Reformation may only stand behind that of Luther himself. As a parish pastor, reformer, diplomat, preacher, and scholar, the former Dominican Bucer would help initiate and stabilize reform throughout the Holy Roman Empire, but chiefly in the imperial free city of Strasbourg. There he would serve multiple parishes, draft liturgies, church orders, and catechisms, and work in tandem with some of the more prominent intellectuals of his day, including Calvin, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, Wolfgang Capito, and Johannes Sturm.

Born November 11, 1491, in the town of Schlettstadt near Strasbourg, Bucer was the son of a poor cobbler. Despite such a meagre pedigree, he was trained at the renowned Latin school in his hometown run by the local Dominican cloister, where he would take vows in 1506 at the age of only fifteen. Proving to be an excellent young student and thinker, by 1516 he was transferred to the Blackfriars house in Heidelberg to continue his education. At Heidelberg, he studied Greek under the future reformer Johannes Brenz and also came under the spell of Erasmus of Rotterdam, the most famous humanist of the day.

It was by chance that Bucer attended the Heidelberg Disputation of April 1518, where Luther delivered his famous theses excoriating medieval scholasticism. The young friar was quickly swayed by Luther’s opinions and, against the objections of his Dominican superiors, obtained a papal dispensation releasing him from his vows. On April 29, 1521, Bucer became pastor at Landstuhl, a parish under the care of the powerful German knight, Franz von Sickingen. He would soon marry a former nun from Lobenfeld, Elizabeth Silbereisen. Affairs at Landstuhl grew tense, however, when Sickingen helped lead the Knights’ War against the elector of Trier. The knights were beaten badly, thereby putting Bucer at risk. Shortly thereafter, he was forced to leave for Strasbourg, but along the way he was enlisted by Heinrich Motherer to help with the work of reform in Weissenburg. During a short stay at Weissenburg, Bucer preached sermons on 1 Peter and Matthew and also drafted his first theological treatise. Nonetheless, the ultimate failure of the knights’ coalition led to his departure from Weissenburg in May 1523.

Bucer finally made his way to Strasbourg and quickly became a leading proponent of reform in the city. He was named pastor of St. Aurelia’s in 1524, serving until 1531. We wrote an evangelical order for mass in 1525, as well as several catechisms for use in instruction. He also became a prodigious biblical scholar during this period. He published Latin translations of Johannes Bugenhagen’s Psalms commentary and Luther’s sermons, and he wrote commentaries of his own on the synoptic Gospels, Ephesians, John, Zephaniah, and Psalms. By 1529, he also persuaded the Strasbourg council to abolish the Roman Mass.

In the same year, Bucer was conscripted into the Protestant controversy over the Eucharist. Though he had once held Luther’s views, he was influenced by Zwingli and Karlstadt to adopt a more symbolic view around 1525, only to finally gravitate toward a mediating position. Nonetheless, despite his own personal rapport with Zwingli, he was not able to bring the Swiss theologian and Luther to agreement at the 1529 Marburg Colloquy. As a result, the various reforming parties could not present a unified stance before the emperor, Charles V, at the 1530 Diet of Augsburg. While the north German princes supported Melanchthon’s Confessio Augustana (Augsburg Confession),and the reformed Swiss cantons threw their lot in with Zwingli’s Fidei Ratio, Bucer drafted the Confessio Tetrapolitana, a statement affirmed only by the four cities of Strasbourg, Constance, Memmingen, and Lindau. He would redouble his efforts to create inner-Protestant unity during the ensuing years. He convinced Strasbourg theologians to subscribe to the Augsburg Confession in 1532, reached agreement with Melanchthon on the Eucharist at Kassel in 1534, and finally broke through to Luther in 1536 with the Wittenberg Concord. The agreement affirmed Luther’s language of a sacramental union of the elements with the body and blood of Christ, then used that to embrace both the Wittenberg insistence on the Real Presence and the Strasbourg emphasis on the mystery of the sacrament and the preparation of the believer for reception.

Back in Strasbourg, Bucer continued the work of reform as pastor of St. Thomas from 1531–40. In 1534, he drafted and had approved an important church order that established the office of church presbyter as a fundamental instrument of church government. While his efforts to establish strict church discipline with his church order failed, he was later able to foster an alternative by supporting small groups of Christians who would meet together to exercise discipline internally and prepare themselves for communion. He also sought to expel Anabaptists from the city, though opposing the more harsh capital measures taken against them elsewhere in Germany. Bucer would remain concerned with education and catechesis. Along with fellow reformer, Johannes Sturm, he turned the old Latin school in Strasbourg into a preparatory school in 1538, later also establishing a seminary with Sturm in 1544. He wrote another catechism in 1534, then in 1539 reinstituted the practice of confirmation for the purpose of catechizing the youth of the city. Outside of Strasbourg, he became exceedingly active in propagating the Reformation. He had a direct hand in starting reform at Ulm, Frankfurt am Main, Augsburg, Hamburg, and Cologne, while also contributing to its adoption and progress in Hanau-Lichtenberg, Baden, Württemberg, and Hesse.

Bucer’s later years, however, saw his influence wane as he suffered failure on numerous fronts. First, in 1540 he joined the heated religious colloquies between Protestants and Catholics that were held at Worms, then the next year in Regensburg. As part of the colloquies, he drafted the infamous “Regensburg Book” with Johannes Gropper, a Catholic theologian from Cologne. The set of doctrinal articles were written in such a way so as to reach agreement with both parties, even resulting in a short-lived settlement on the doctrine of justification. When talks broke down over questions of church authority, however, the colloquies fell apart. In 1543, Bucer was appointed preacher in Bonn by Hermann von Wied, archbishop of Cologne, to help reform the diocese. He was again defeated, this time due to opposition from his former collaborator at Regensburg, Gropper, who refused to allow Cologne to go Protestant. Finally, back in Strasbourg Bucer found a new opponent in Charles V. Having emerged victorious in war with the Protestant Schmalkaldic League, the emperor instituted the 1548 Augsburg Interim, which forced Protestants to return to Catholic practice with very limited concessions. Bucer led the charge in Strasbourg to resist the emperor, but Johannes Sturm—again, a former colleague—negotiated a settlement with Charles against Bucer’s wishes. As a result, Bucer was forced to leave Strasbourg, never to return.

In 1549, Bucer made his way across the English Channel to London, where he would spend the remaining two years of his life. He lectured at Cambridge, assisted Thomas Cranmer in revising the Book of Common Prayer, and composed his own magnum opus, De Regno Christi. In De Regno Christi, Bucer laid out his vision for the reform of both the British church and the British government. The work was received with great acclaim by King Edward VI and led to a doctor of divinity awarded by Cambridge, but soon after its completion Bucer fell ill. He never recovered, dying on February 28, 1551, and receiving committal at Great St. Mary’s in Cambridge. After Queen Mary rose to the throne, she exhumed his remains and had them burned in 1556. Following Queen Elizabeth’s accession, however, she rehabilitated him by ceremony in 1560.