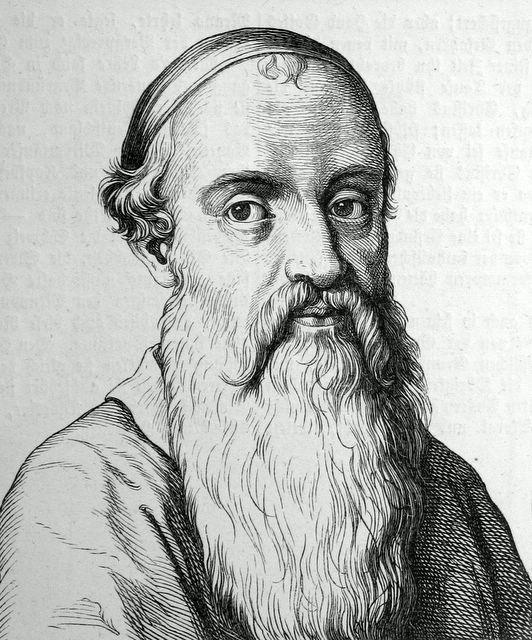

While many of the so-called “radical reformers” took up arms in their fight for ecclesiastical and political independence, Menno Simons came to teach a pacifistic Anabaptism. A priest who remained an active reformer in the Dutch Catholic churches well after his conversion to evangelical doctrine, Simons shaped a new direction among Anabaptists that would prove theologically influential in later days. He is the father of the modern Mennonite (from his surname, “Menno”) and Amish communities, who continue to espouse his pacifism and his emphasis upon the new life in Christ.

Born in 1496 to a Dutch dairy farmer in Witmarsum, Friesland, Simons received very little structured education, possibly studying at a monastery school in nearby Bolsward, but never theology at the university level. Nonetheless, he became proficient in Latin and also learned Greek. In 1524, he was ordained vicar in Pingjum, Friesland, his father’s native village. Simons most likely worked under another priest in preparation for ordination, but with no formal theological education he later admitted that he did not actually read the Bible until 1526.

During his time at Pingjum, the Protestant Reformation had begun to make headway in the Netherlands, though Simons’s knowledge of the early debates and writings is questionable. Scholars suggest that his own early misgivings about the medieval mass coincided with the spread of anti-sacramental ideas in the region, in particular those of Hinne Rode. It was Rode who wrote in criticism of the sacramental teachings of both Rome and Wittenberg, even apparently attempting to convince Luther. Simons almost certainly read Rode and soon became a committed opponent of transubstantion. Despite his acceptance of evangelical doctrine, he remained in the Roman church and actively supported its reform.

In 1531, he left Pingjum for his home, Witmarsum, where he was named priest. It was there that he finally rejected infant baptism under the influence of Dutch followers of the German Anabaptist Melchior Hoffman. He continued his advocacy of reform and his support for the Anabaptist movement until a fateful event led him to take his theological convictions in a different direction than his colleagues. In April 1535, Simons’s brother, Peter, along with a number of other Anabaptists took over an area monastery. Due to the insurrections attempted by various radical groups in the previous decade or so, not to mention the threatening rhetoric of contemporary Anabaptists such as Jan Matthijs and Jan of Leyden, there was considerable pressure to act preemptively against them. The authorities laid siege to the monastery and killed its occupants, including Peter Simons. The entire episode, in conjunction with repeated attempts by authorities to link his own more conservative Anabaptist theology with the radicals, led Menno Simons to chart a different course for his reforms. He began teaching a pacifistic rather than revolutionary brand of Anabaptism that put a greater emphasis on repentance and the new life, not apocalypticism, economics, or questions of authority like his peers.

Simons pressed his reform efforts further in Witmarsum until January 1536, when he left in the hopes of encouraging Anabaptists elsewhere to accept his pacifistic ways. He first joined the Anabaptist community in the province of Groningen, where he was soon rebaptized and a year later ordained as an elder. This period proved to be his most influential. In addition to routine visits of Anabaptists in Friesland and Holland, he found time to compose numerous treatises, including The Spiritual Resurrection, which paralleled the believer’s new life with Christ’s resurrection, the Augustinian-influenced Meditation on the Twenty-Fifth Psalm, and The New Birth (1537), an exhortation to repentance and regeneration rather than slavish obedience to laws. But the most significant of all his writings was 1539’s The Foundation of Christian Doctrine. His magnum opus laid out a reinterpretation of Anabaptism, bringing together traditional Catholic spirituality with Erasmian pacifism, yet rejecting the medieval sacramental system.

With his thoughts in print and his influence rising, Simons became a target for ecclesiastical authorities and repeatedly had to uproot his family due to governmental concern over his teachings. In 1542, Charles V published an edict demanding the reformer’s arrest. He did find a hospitable diocese in Cologne under the reforming bishop Hermann von Wied, where he lived from 1544 until 1547. Wied’s replacement, the more conservative Adolf von Schaumburg, forced him to flee again. Shortly thereafter he would settle in Schleswig-Holstein and, after a decade worth of itinerancy, remain until his death. Still suspected of the radical tendencies that characterized many other Anabaptists, Simons was regularly forced to defend himself against the accusations. Ironically, he found himself in conflict with many such radical Anabaptists. In 1550, he drafted Confession of the Triune God, a polemical repudiation of an Anabaptist pastor’s skepticism regarding the divinity of Christ. During his time at Schleswig-Holstein, he also came to emphasize church discipline to a much greater degree as an antidote to the spiritualizing tendencies of other Anabaptists, such as the Dutch radical David Joris.

After a long stay in Schleswig-Holstein, fraught with much illness and the thorough crippling of his legs, Simons died on January 31, 1561. Though his literary output was not as voluminous as other leading reformers, such as Luther, Zwingli, or Calvin, Simons nonetheless left his theological stamp on the Protestant Reformation and his teachings would live on in the Mennonite and Amish communities for centuries. His pacifistic interpretation of Anabaptism marked a stark departure from more politically radical predecessors, while his emphasis on repentance, regeneration, and the new life in Christ rooted Anabaptism in a more traditional spirituality.